-

The Baptist Church

Baptist Churches began in 1612, among English refugees living in Holland. They were unwelcome in England due to their non-participation in the Church of England. This was the same group that became known as the Puritans who landed at Plymouth Rock. In New Hampshire, the first congregation was established in 1751, and by 1809, there were churches in Weare, Temple, Mason, and Dublin. The time was ripe for the formation of a Baptist Church in Bennington — except that there was no Bennington then.

A Baptist Church was begun in Greenfield. They met at Joseph Eaton’s house on December 17, 1805. They called the new entity the “Peterborough and Society Land Baptist Church.” The Eaton house was in Greenfield at the time, but when the borders of Bennington were drawn, that part of Greenfield became part of Bennington. Among the early members were John Colby, Joseph Eaton, Benjamin Nichols, and Isaac Tenney, along with some wives and daughters, and they all became Bennington residents when the borders changed. On the 19th of August, 1824, the name was changed to Society Land Baptist Church. At last, Bennington was formed in 1842, and the name of the congregation became the Bennington Baptist Church.

Church services were held in a barn, but it is unknown where it was located. Surely it was in the Village, as down-town Bennington was called. Earliest ministers were chosen from among the Elders of the church: Elders Elliott, Westcott, Farrar, Goodnow, McGregor and Joseph Davis. After a while, ordained ministers were called to serve: Reverends J.A. Boswell, F. Page, John Woodbury, Zebulon Jones, Amzi Jones, J.M. Chick, S.L. Elliott, and W.W. Lovejoy.

During Rev. Lovejoy’s tenure, a big decision was made. In January, 1852, the Bennington congregation decided to rent Woodbury’s Hall, at Antrim for their meetings. Why? Did the meetinghouse roof leak? Was the building in Bennington too small, or too drafty? Had the road along the river toward Antrim been improved? A month later, the group voted to hold all their meetings in Antrim, and five years later, they were calling it the Antrim Baptist Church.

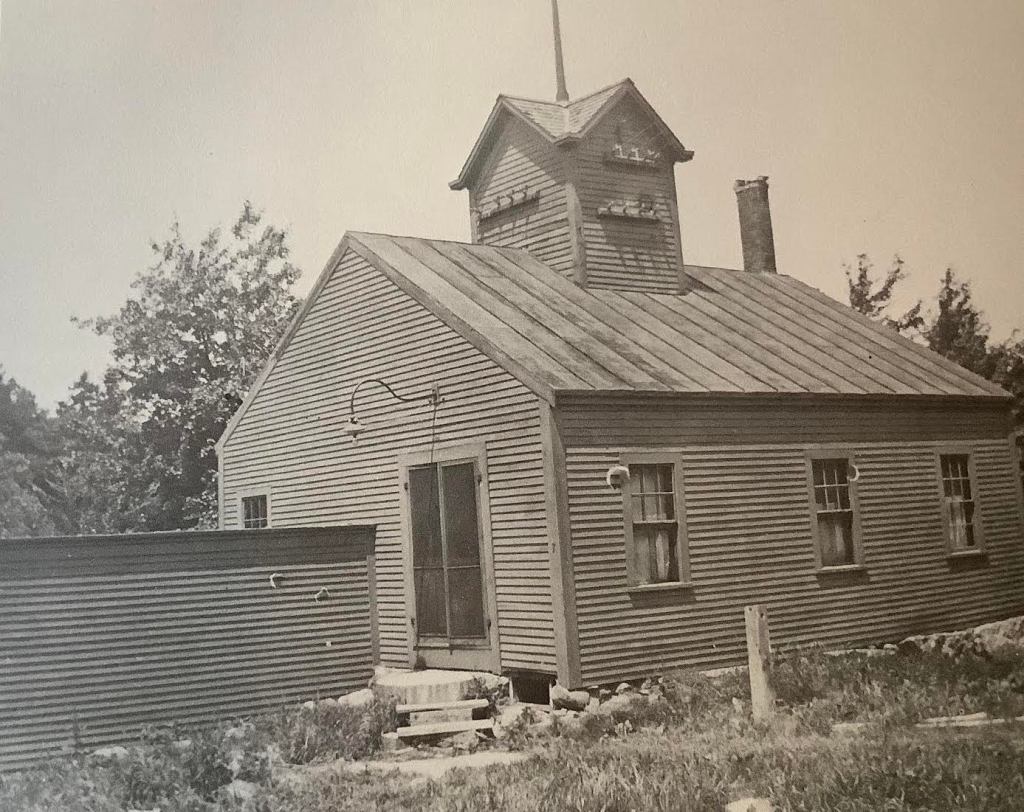

The barn of the house at 27 Bible Hill Road was once the Bennington Baptist Church.

The photo shows the barn at the rear of the house, projecting off to the right.In those days, an unused, unclaimed structure was often moved to another location and repurposed. The former Bennington Baptist Church building was moved from its original location to become the barn of the house at 27 Bible Hill Road. It is still there today.

The next installment of the Bennington NH Historical Society Blog will be posted on January 1, 2024. If you click the Follow button, all future posts will be sent straight to your inbox every month.

-

Bennington Architecture: the Colonial

One can tell a lot about the economic history of a community by looking at the houses. If one style predominates, that reveals when the fortunes of the town were at their peak. Architecture styles change over time, showing the preferences of the people based on convenience, availability of materials, and outside influences. Bennington is no different, as eight distinct styles were employed from late 1700s to the 1950s: the Cape; the Colonial; the Federal; the American Gothic; the Italianate; Second Empire; the Queen Anne; and the Ranch.

The ‘colonial era’ in New England ran from 1607 to 1776. One speaks of ‘colonial architecture,’ but only one type of house is called The Colonial. It is rather like a grown up Cape-style house. Sometimes a standard Cape would be enlarged by putting on a second floor, turning it into a Colonial. A ‘Colonial’ is a two-and-a-half story house in a rectangular shape. The facade has five windows on the second floor and two [sometimes one] on each side of the centrally-placed front door is on the long side of the house. It is the classic farmhouse of the New England country-side. Inside, there is an entry hall, dominated by the ascending staircase. To the left would be a parlor, and on the right, the dining room. The kitchen is in the back of the first floor. Upstairs, there would be a hallway and four bedrooms, one in each corner.

Chase homestead on Route 202

Curtis Homestead on North Bennington Road The next installment of the Bennington NH Historical Society Blog will be posted on December 11, 2023. If you click the Follow button, all future posts will be sent straight to your inbox every month.

-

The Train Station

In the 1800s, when the train tracks were laid down in New Hampshire, a town would be very glad to get a station on the line. Not to have access to a line was to go down the path to obscurity. As the century progressed, train lines were formed, and merged until much of the state was covered. The Northern Railroad Company was founded in 1844 and by 1881, track was in place to run along the Contoocook River, from Peterborough to Hillsboro. [Hillsboro used to be Hillsborough, but the railroad shortened it to fit on signage. Peterborough insisted on the longer name.]

Railroad map from 1894, showing Bennington with neighbors. Every town along the line wanted a station — for shipping goods and especially to deliver fresh milk to creameries in the cities. Not every town was lucky enough, but Bennington won the lottery with three stations!

One was on North Bennington Road, where Tenney Farm grows corn now. Although in Bennington, this was officially the Antrim, NH station, since that was the closest that a stop could be located near the center of that town. Both passengers and freight were handled there, but perhaps its chief function was collecting milk. Farmers would come from West Deering and from across the river to get the milk to the train every morning. Some buildings along the track were still there in the 1970s, but they are gone now.

The official Bennington station was near the center of town, between the track and the River. One could get on the train there and have access to Nashua in the South, via a stop at Elmwood Junction in Hancock, or go to Concord in the North, with a stop in Hillsboro.

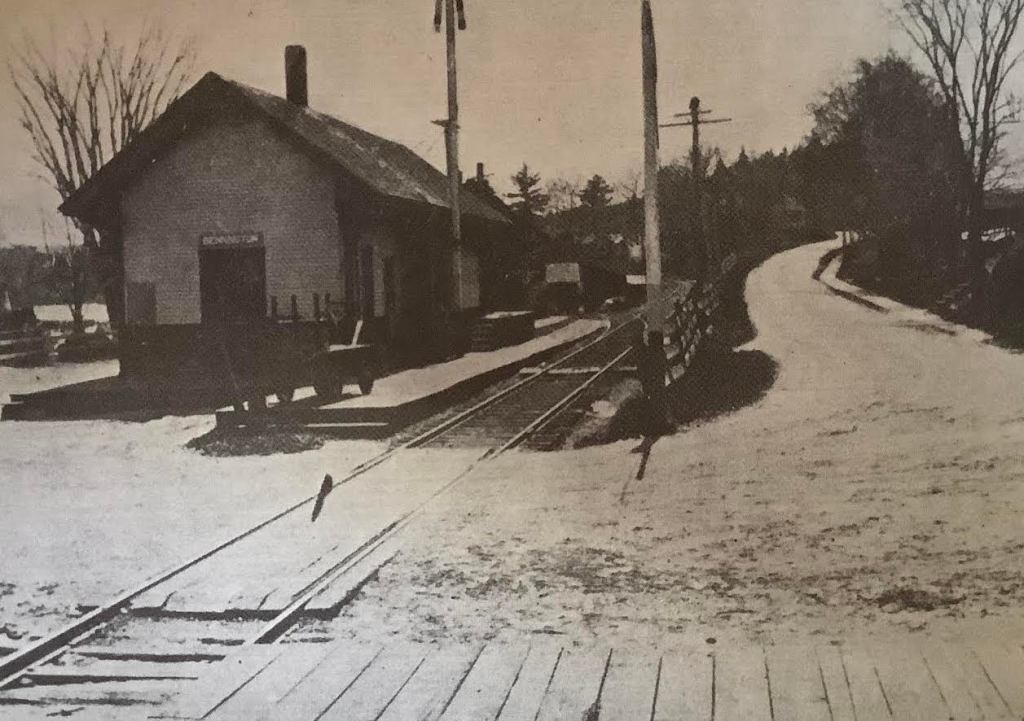

This is the principle train station for Bennington, at its original location between Hancock Road and the Contoocook River. Here we see it from the North around 1900. The third station was on South Bennington Road at the Greenfield town line. This little station was primarily a milk stop, and as soon as trucks began to transport milk, the station was closed. If you lived in South Bennington and you wanted to go into the Village, you could flag down the train along the line and hitch a ride. Many students from Bennington went to high school in Hillsboro because it was easier to take the train to there than it was to get to the school in Antrim. Nada Wilson Huntington was one of them, since her family lived next to the track.

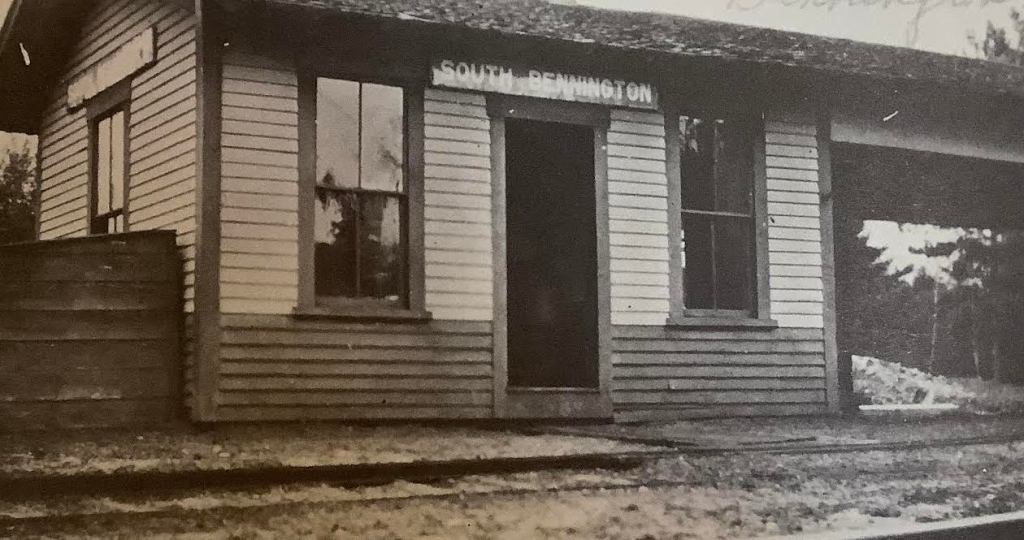

South Bennington Station. In 1906, the line running through town was the Boston and Maine Railroad, due to a merger, and so it remained until the formation of the Milford-Bennington Railroad Company in 1987. That company hauled sand and gravel to Wilton. One evening, the train stopped on the track so that the engineer and brakeman could cross Route 202 to have dinner at the Powder Mill Pond Restaurant.

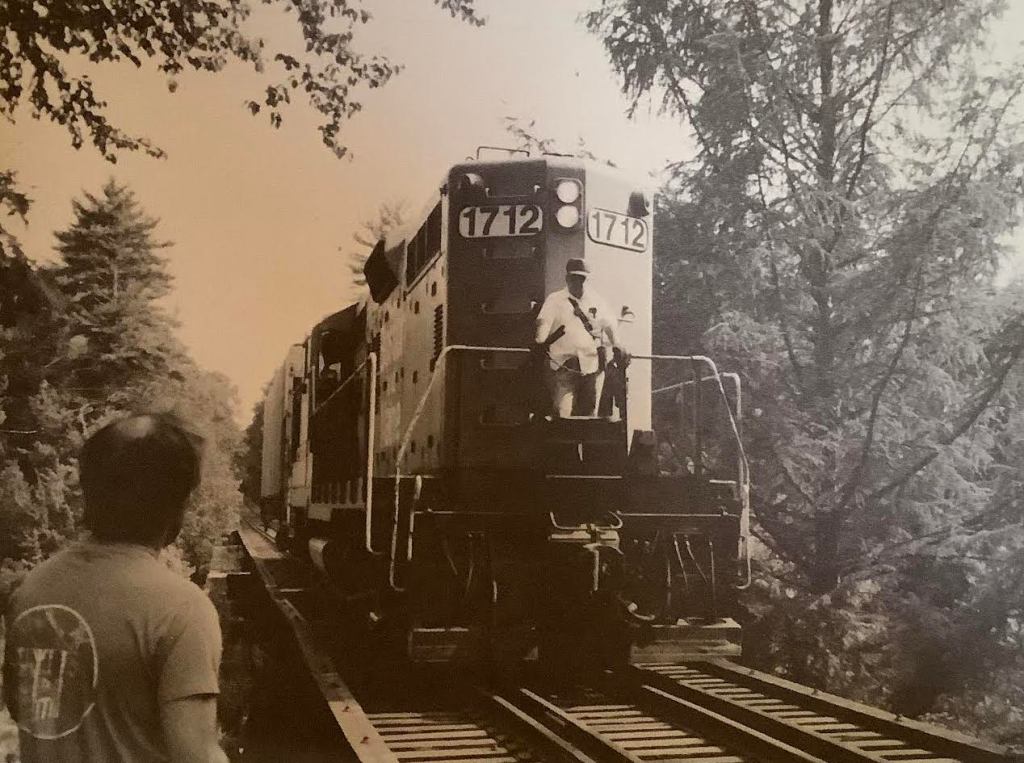

On May 26, 1986, the last regularly scheduled train came through Bennington. Today the main station is located across the street and a little bit North of its original location. It is currently the VFW Hall and is used as a meeting space for town groups. Most of the train tracks in Bennington were torn up and where steam engines once charged along, now walkers, cyclists, and snowmobilers roam under leafy canopies.

Where the train station used to be, looking South along the track, with Hancock Road on right.

The train station in its new location, and in its new use as VFW Hall and meeting space. The next installment of the Bennington NH Historical Society Blog will be posted on November 13, 2023. If you click the Follow button, all future posts will be sent straight to your inbox every month.

-

The Walking Stick

What do Lady Danbury, Beau Brummell, Johnny Walker, and Louis the 14th all have in common? They all wear a walking stick.

Louis XIV, who was proud of his shapely legs, introduced the cane to court.

Lady Danbury from Bridgerton actually uses her cane.

Johnnie Walker, icon of a whisky brand, wears his cane with verve. A walking stick, as a prop for tired legs, has been around for millennia. In the Middle Ages, it was often called a ‘Pilgrim’s Staff’ since it was carried by those who trudged 100s or 1000s of miles to visit a holy shrine. But the Walking Stick as a fashion accessory perhaps came into use in the 1600s.

The French King Louis XIV was worried about assassins, so he banned the carrying of swords in court. Since gentlemen were in the habit of resting their left hand on the pommel of their swords, they now had nothing to do with their hands. A decorative staff, the length of a sword and with costly embellishments, became the substitute, and a fashion trend was born. The custom moved to England and by the early 1800s, both men and women were sporting them. The term of use was “to wear” a walking stick or cane, not “to carry” it. Indeed, these sticks were rarely touching the ground, most were too short to use as an actual cane — they were pure fashion.

The fashion continued late into the 1800s in the United States. [My great-grandfather in Pennsylvania had an ebony cane with an ivory knob.] This all lead to a brilliant marking ploy for the Boston Post newspaper. In 1909, sales needed a boost, so the publisher, Edwin A. Grozier, devised the idea of a ceremonial cane to be awarded to the eldest male resident of 700 towns in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. The canes were made of ebony by the J.F. Fradley company of New York. Each cane had a gold knob proclaiming it to be the gift of the Boston Post.

This Boston Post Cane is from Maynard, Massachusetts. The canes were sent out to each town’s Board of Selectmen, who were to identify the oldest man in town and present the cane to him, with appropriate pomp. At first, this was seen as a great honor, but problems loomed. Several recipients’ families though that the cane was a gift and belonged to his survivors, despite the words “TO BE TRANSMITTED” engraved on the knob. The cane was supposed to be returned to the Select Board for reassignment, and this lead to some uncomfortable situations in many towns.

Then there was the fact that the Oldest Citizen would at some point die. So many cane holders died within months or weeks of receiving it, that the Cane was viewed as a curse. Some citizens refused to take it, leading to years with no one holding the Cane. Eventually, the Oldest Citizen was permitted to be a woman, thus the Cane could go to the actual eldest person in town.

Over the years, many of the original 700 Canes have been lost [in house fires] or stolen [watch for them in antique stores and alert the town named on the knob] or broken. There are 517 towns that still have an original Cane, Bennington, New Hampshire included. Many towns, wishing to preserve the tradition, have made replicas of their cane, keeping the original in the town’s museum and awarding the replica. Bennington’s original Boston Post Cane may be seen at the Historical Society. The Boston Post newspaper was last seen in 1957, but the Boston Post Cane lives on.

Cane Holders in Bennington: 1909-1915 Willard S. Carkin His widow did not want to give it back. 1915-1921 John Milton Bartlett 1921-1940 Thomas Wilson 1940-1944 Jerome Sawyer 1944-1948 Edward Newton 1948-1959 George Holmes 1960-1961 Minnie F. Cady, first woman in town to hold the Cane 1961-1964 Edith Lillian Lawrence 1964 J. Harvey Balch received the Cane, but turned it in when he moved to another town in an unknown year. ??-1983 Lena Tayler/Taylor was next, but she moved to Pennsylvania in 1983, so she turned in the cane. 1983-1984 Marion L. Griswold 1984-1984 Theresa Cashion Gibson, who beat out her closest age-mate, Mrs. Vivian Stimson, by being 2 days older 1984-1985 Vivian Stimson 1985-??? Margaret Sawyer, daughter-in-law of Jerome Sawyer, see above 19?? Margaret Sawyer’s brother-in-law, making three in one family! 198?-1994 Francis H. LeBlanc 2022 John Ferranti

John Ferranti shows off the Bennington, New Hampshire replica of the Boston Post Cane. The next installment of the Bennington NH Historical Society Blog will be posted on October 23, 2023. If you click the Follow button, all future posts will be sent straight to your inbox every month.

-

Immigration to Bennington

On page 38 of the History of Bennington, NH, there is a list of ‘the early settlers’ of the area that is now Bennington. A look at that list shows the names of such large property owners as Dodge, Colby, Huntington, Butler, Fleming, and Whittemore. What do we notice about this list? Of the 40 names, two are most likely of Scottish origin, one is probably French, one is probably German, and the other 36 are English names. They had moved to here from other places in New Hampshire, drawn by the water rushing over the Great Falls of the Contoocook, looking to make their fortunes.

Of course those names were not native to North America, they came from Europe originally. Why? Economic opportunity, personal freedom. But what about the people who’s names were not listed as founding fathers? There were wives, surely, with their own countries of origin. Were there servants or enslaved people? We do not know about them, but the Town History also tells us that there were “Irish laborers” here too.

This is the story of people who left their homes and families and nations of origin to journey to America. Why? For the same economic opportunity and personal freedom that brought the Dodges and the Huntingtons. The data for this paper is taken from Town Reports kept at the Historical Society. We have them going back to 1866, only 24 years after the town was founded. But the reports that survived from 1866 to 1887, do not include vital statistics. From 1888, the town included births, marriages, and deaths in the annual lists and those told where people in the town were born. From those listings, I have put together the story of immigrants who came to Bennington.

1889 is the first year for which we have proof of immigrants arriving in town: two from Scotland, one from Ireland, and three from Germany. At that time Scots were being recruited to work in factories all over New England. In 1890, there is evidence of only one person of foreign birth in Bennington – Arthur Pierce, who went on to own the paper mill, was born in Erzoum, Turkey, even though his family was not Turkish.

From 1891-1895, the pace of immigration picked up. Ten Scots, seven Irish, three Germans might be expected, echoing the 1889 numbers. Scotland and Ireland were still ‘exporting’ citizens, the economies of those countries unable to supply jobs to applicants. The German economy and political situation were also dire, prompting 5 million Germans to enter America during the 1800s. In addition, eight residents of Switzerland moved here as part of an exodus of 89,000 people. At the same time, we see the first Canadians appearing: eight, half from Nova Scotia and the rest not specifying a province. Canada was having tough economic times, too. The factory jobs in New England were more attractive than subsistance farming at home.

In the second half of the 1890s, America’s ‘Guilded Age’, Switzerland topped the list, with 10 new arrivals. Next was Canada: one from Nova Scotia, six from elsewhere. Here is a classic example of a ‘chain migration.’ In 1891, Fred Mallett arrives from Digby, Nova Scotia, followed in 1892 by Eli and his wife. Then two years later, along comes Phillipe Mallett. In 1900, W.F. And Oscar Mallett join them. It was typical for an older brother to migrate first, get a job and a place to live, then send for the next brother, and the next. In the same timespan, an English citizen, five Irish and three more Germans came to town.

The turn of the new century brought prosperity in town, and lots of new immigrants. Canada lead the way with six new residents [two from New Bruswick], with Ireland, Switzerland, and Italy tied at two each in the first five years of 1900. 1903 marks the first arrivals of Italians to Bennington. 1905-1909 shows a sharp uptick in arrivals from Ireland and Canada, with six each. In 1907, we see the first known arrival from Prince Edward Island, Canada. It was a woman, who followed a typical immigration history: her family from Ireland moved to PEI, Canada. Then Miss Muray traveled to Boston, and thence to Bennington. During the early 1900s, Bennington saw citizens from 13 countries, including France, Holland and Denmark.

From 1910 to 1914, there was a boom in immigration from Italy and also Ireland. A familiar name shows up in this time: Joseph Cuddemi, Sr. arrived in 1912. Greek migrants show up in 1910. There was a chain of Swiss migration and a chain of Irish family migration too.

From 1915 to 1919, the Irish are still moving in large numbers followed by Canadians, Italians, and Greeks. But the big influx of Greek immigrants arrives in 1920. They are listed in the Town Reports as having jobs in the paper industry. [Starrett Road was nicknamed “Greek Alley” because of immigrants living in company housing on that street. The name, considered to be an ethnic slur, is not used anymore.] In the 1920s, 24 people are listed with a Greek place of birth. Nine other countries are represented as well. In 1926, Steve Zachos arrived, followed by Costas Zachos in 1929.

War rumors and the Great Depression no doubt suppressed immigration from Europe in the 1930s, or else people were not permitted to travel. Only 35 new citizens from foreign countries arrived in our town during that decade. Among them are Arnie Cernota’s parents, Paul and Mary from Czechslovakia.

Overall, in the first 100 years, Bennington benefitted from the arrival of many new people. Some people say that immigrants are a bad thing. Really? Think how our town would be without the Cuddemis, the Zachoses, the Cernotas, the Clearys, the Cashions, and all the other people who came from diverse nations to make Bennington their home.

The text of this blog had been the topic of a presentation to the historical Society.

The next installment of the Bennington NH Historical Society Blog will be posted on October 17, 2023. If you click the Follow button, all future posts will be sent straight to your inbox every month.

-

Bennington Architecture: the Cape

Architecture styles change over time, showing the preferences of the people based on convenience, availability of materials, and outside influences. Bennington is no different. From the late 1700s to 1910, there were eight recognizable styles of houses were built in our town. The oldest is the Cape.

House Beautiful.com describes a Cape-style house this way: “…modest, one-room deep, wood-framed houses with clapboard or shingle exteriors (which, when weathered over time, turned that quintessential light gray color). They were low, broad structures with unadorned, flat-front facades….The classic Cape Cod cottage had a central front door with two windows on each side of it…The homes often had a large central chimney that linked to several rooms in the house, with a steeply pitched, side-gabled roof (meaning the triangular portions of the roof are on the sides of the house), which helped prevent snow accumulation. The ceilings of the single-story homes were low, which kept things cozy and also helped to keep living quarters warm.”

The oldest houses in Bennington date from the 1790s, and they are all Cape-style. It is said that many of the houses on Main Street were built by John Putnam, to encourage families to move to the area.

From OldHouseonline.com The floor plan at left shows the typical lay-out of the time: only three main rooms downstairs, around the central chimney. A ‘keeping room’ would be called the kitchen today or a ‘great room’/family room in modern decorating parlance. It was the warmest room in the house. That was where the cooking, eating, and everyday life occurred. The four rooms flanking the keeping room were for two pantries; a bedroom for a guest; a smaller bedroom for a family invalid, or servant. The stairs lead to a loft for storage and for children’s sleeping quarters as the family grew.

Balch Farm House We are fortunate that some of our oldest houses still stand, such as the Putnam House; Balch Farm house near the top of Bible Hill Road [which was being restored in 1979, when it caught fire from a purported lightning strike, and was almost completely destroyed]; and the many Cape-style houses near the Village Center, like the one below on Bible Hill Road, sometimes called the Burtt House, after its builder.

One of two old Capes, almost across the road from each other, on Bible Hill Road near the Village Center. The next installment of the Bennington NH Historical Society Blog will be posted on September 18, 2023. If you click the Follow button, all future posts will be sent straight to your inbox every month.

-

The Band Stand

On the Common of many towns in New Hampshire there stands a recognizable structure. It is round or hexagonal or octagonal; it is elevated above ground, reached by several steps; it is roofed but is open to the air on all sides; there is a railing around the edge. What is it? It is a Band Stand. Or is it a Gazebo??

This yard feature, seen at people’s gardens, has been around for 1000s of years. The nature-loving ancient Egyptians 5000 years ago built small, roofed structures in their gardens. Covered with vines, they were designed for sitting in the shade and looking out over water. It was such a nice idea that the Persians and Greeks built them too. The Persians loved to entertain in their garden-houses, even ratifying peace treaties and negotiations in those spots. The Greeks built small, roofed structures of marble near temples for holding religious rituals or just socializing. The trend went East, and turned into locations for the tea ceremony in Japanese gardens. These buildings had various names in their local languages.

In the 1300s, the French popularized little structures outdoors, and eventually the English followed suit. From the early 1800s, English gardens were fanciful recreations of the untamed side of nature: twisting paths through the woods lead to a spot where there was a view. And there you would find a small shelter for sitting and gazing. Some say this is the origin of the word ‘gazebo,’ a word that came into vogue then.

In the early 1800s, the Industrial Revolution turned large market towns into big factory cities filled with slums and poverty. Social Reformers looked for ways to cut down on crime by giving people some wholesome entertainment, and band concerts were the answer. Churches and social clubs formed bands, and since they needed a place to play, bandstands were built. When the city of Manchester, NH was planned, there were many parks [or ‘squares’] and each contained a bandstand. After the Civil War, returning soldiers formed ‘Cornet Bands’ in many towns.

The late 1800s and early 1900s were the heyday of the small town band, of which the Temple Town Band is the oldest example. Towns hurried to build bandstands for their own local bands, and for touring musicians to give concerts. In Bennington, a bandstand was built on the grassy common in front of the Congregational Church in 1895. There was a town celebration for the dedication of this new civic structure. Around that same time, electricity came to town, in the form of street lights. The peak of the bandstand’s roof took the place of a pole for one span of electrical wires.

The Bennington Bandstand-cum-electrical pole in its original location in 1895. In 1949, the decision was made to move the Civil War Monument from the middle of the Main Street-Francestown Road intersection to a spot closer to the Church. To make room for it, the unused, slightly derelict old bandstand was torn down. It had long been the dream of Historical Society founder David Glynn to rebuild the Bandstand, sometimes called the Gazebo. In 2020, money provided by a bequest from Mr. Glynn, made a new bandstand/gazebo possible, but not in the same old location. Land across from the Dodge Library, at the intersection of Main Street and Greenfield Road, was purchased jointly by the Historical Society, the Library, and the Congregational Church.

Is it a bandstand or is it a gazebo? Think of it this way: ‘gazebo’ describes a particular type of structure, and if you put musicians in it, it becomes a ‘bandstand.’

-

The Congregational Church

When Bennington, New Hampshire was just a cluster of raw-wood houses in the 1790s, there was no place to go to church. When the area was called Factory Village, a family could journey to attend the Congregational Church of Hancock, but that was a long trip, impassible in winter or Mud Season. Most families probably held home-based religious activities on Sundays: prayers, scripture readings, hymn singing. In 1833, a group of town worthies banded together for worship as the Union Trinitarian Congregational Society, meeting in private homes for worship.

From then on, there was a push to build a church to serve those who lived on the banks of the Contoocook River. Congregationalism as a church movement, descended from Puritans who thought that each church should run its own affairs, unbeholding to the dictates of people elsewhere. By that time, citizens of what-would-become Bennington were feeling stirrings of independence, so a Congregational church would have been a good fit. Evangelical churches [Congregational, Methodist, Presbyterian] were part of the Second Great Awakening of religion in the1800s in the US. This lead to buildings that were not ornate and soaring, like Gothic or Georgian-style churches.

The church building was constructed in the Village Center on the corner of Main Street and Francestown Road in 1839. To pay for it, families would pledge money and sweat-equity to put up the House of God. The style is a simple, gable-end structure. The steeple was the tallest structure in town. A pair of front doors lead into an entry vestibule, thence into the nave. Oddly, the boundary line between the Town of Hancock and the unincorporated Factory Village ran right along the front of the building. When entering the church, one stepped out of Hancock and into Factory Village.

Winter view of the church, most likely from the early 1900s. Note the electric lines and the attached vestry at back.

Church before 1947, with old Vestry as the small building on the left. The nave is a 58’x50′ rectangle with a high ceiling. There was a balcony in the back where the choir sat. At first, there was no church organ and music was provided by two violins and a viola. Coming to church was often the social event of the week. There were two 90-minute services each Sunday, with an hour break in-between. During that time, the children attended Sunday School, everyone had lunch and a good tongue-wag.

The Parsonage, 1884. In 1984, a parsonage was built by George Burns. Some of the ministers of the church included: Rev Ebeneezer Coleman; Rev. Albert Manson; Rev. James Holmes; Rev. Josiah Heald; Dr. Thomas Billings; Rev. Reginald Merrifield; Rev. William Clark, Jr; Rev. Marie Tolander; Rev. Fay Gemmell; Rev. Daniel Poling.

In 1853, a subscription was held to buy a bell for the steeple. In 1896, the small vestry building across the street was abandoned in favor of a set of attached rooms at the back of the church: kitchen, ladies’ parlor, wash room, small chapel. In 1899, a reed organ was installed. In 1917, a clock was donated for the steeple. The church interior was changed in the 1970s. With the lowering of the ceiling, the balcony was walled off.

For Decoration Day, c.1900, the ladies of the G.A.R bedecked the church. Today, the church still holds services, with a revolving slate of ministers. The parsonage was sold off in 1977.

The next installment of the Bennington NH Historical Society Blog will be posted on July 31. If you click the Follow button, all future posts will be sent straight to your inbox every month.

-

Summer People

Since ancient times, the wealthy of the cities would flee to the hills of the countryside in the summer for a cooler, leafier life. In New England, one knows of Newport, Rhode Island and the Berkshires of Massachusetts as being the resorts of the rich. Add to that, Bennington, New Hampshire. There were the hotels in the Village Center of course, the Adams Hotel and the Crystal Springs Hotel, but there was also a thriving business of farms that took in Summer People.

A summer sojourn in the country took on a new impetus in the mid-1800s, as popular novels [Heidi, Secret Garden], medical professionals [Florence Nightingale], and social reformers [Fresh Air Fund] touted the healing powers of nature and the importance of fresh air. The growth of railroads made travel to ‘remote’ areas possible.

After the Civil War, farming slumped in northern New England, so a new income stream was devised. Farm wives were accustomed to cooking for large groups: their family, the laborers who helped with farm work — so why not take in summer borders? As people came from the cities in the summer, farms added a wing of rooms to accommodate them. Meals would be served communally three times a day, and transportation to and from the railroad station was provided. What did the Summer People do all day? Read on the veranda, take nature walks, pick berries, write letters, and relax. Among the farms that took in visitors were the Dodge House atop Dodge Hill Road, with panoramic views:

The Dodge House, now owned by the Warren Family, was the largest and oldest farm in town. The extensions to the original late 1700s farmhouse were added in 1878 and 1884. Colby-Green near-by on Larkin Road:

Built in 1795, the Colby family built the porch in the 1880’s and advertised as a summer resort called Colby-Green. and Favor Farm on the Francestown Road with views of Crotched Mountain.

Favor Farm, is said to have been built from a kit — the sort that Sears Roebuck would send to you. Later, the Blanchard Family farmed here. On the shores of Lake George [now called Lake Whittemore], were children’s camps. Tall Pines was founded by three siblings of the Reaveley family from Gloucester, Massachusetts in 1915. The clientele were the daughters of wealthy Bostonians who were sent to bucolic Bennington for an abundance of fresh air. Their summer included the arts, waterfront activities, hiking, theatricals, vegetable gardening, and ‘some form of useful work.’ The foci of athletics and the arts were always backed up by the emphasis of lots of fresh air– as seen in the windowless dining hall. The camp was damaged by both the Depression and the Hurricane of 1938, and attendance waned.

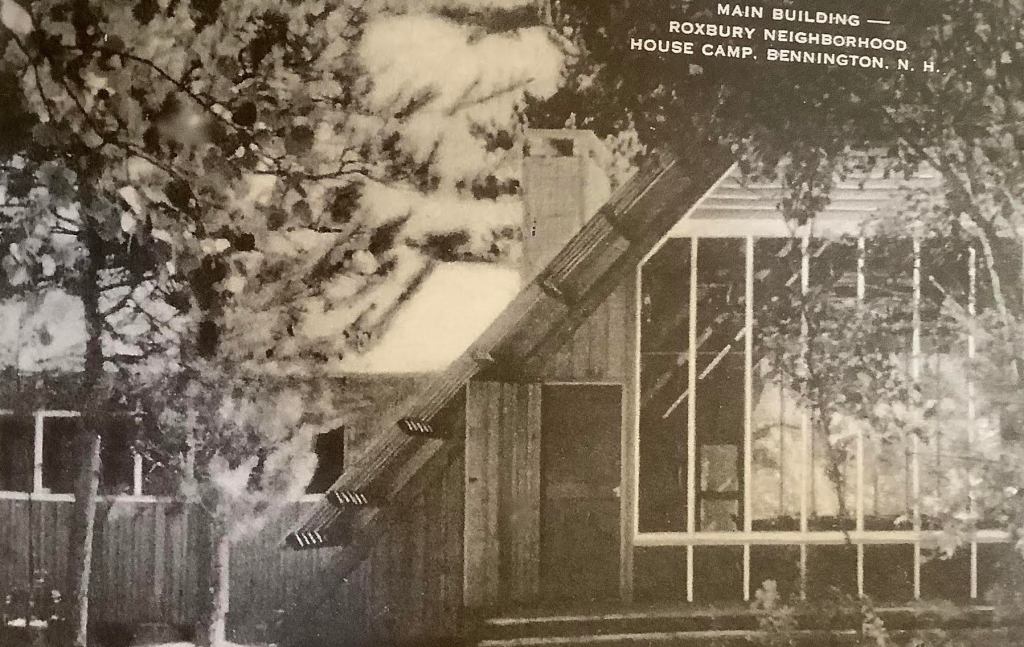

Next door, but culturally miles away, was the camp established by the Roxbury Neighborhood House of Roxbury, Massachusetts. The 120-acre location was bought by philanthropists who deeded it to the social reformers in Roxbury in 1914. They developed a camp where inner city children would stay for two-week sessions, serving 40 campers at a time in multiple encampments. This was a chance for under-privileged children to experience some carefree summer fun aways from the crowded city. Sometimes their mothers came for two or three day vacations. The racial tensions of the 1960s caused the Neighborhood House to change its focus, and the camp closed.

The next installment of the Bennington NH Historical Society Blog will be posted on July 11, 2023. If you click the Follow button, all future posts will be sent straight to your inbox every month.

-

Electric Lights

When did electricity come to your town? Perhaps in 1936, when the US government passed the Rural Electrification Act, which brought up-to-date electricity to many far-flung locations. In 1882, Appleton, Wisconsin saw the first hydroelectrically-powered home, demonstrating the potential of local energy generation. Did you know that Bennington, New Hampshire was a pioneer in electric street lights?

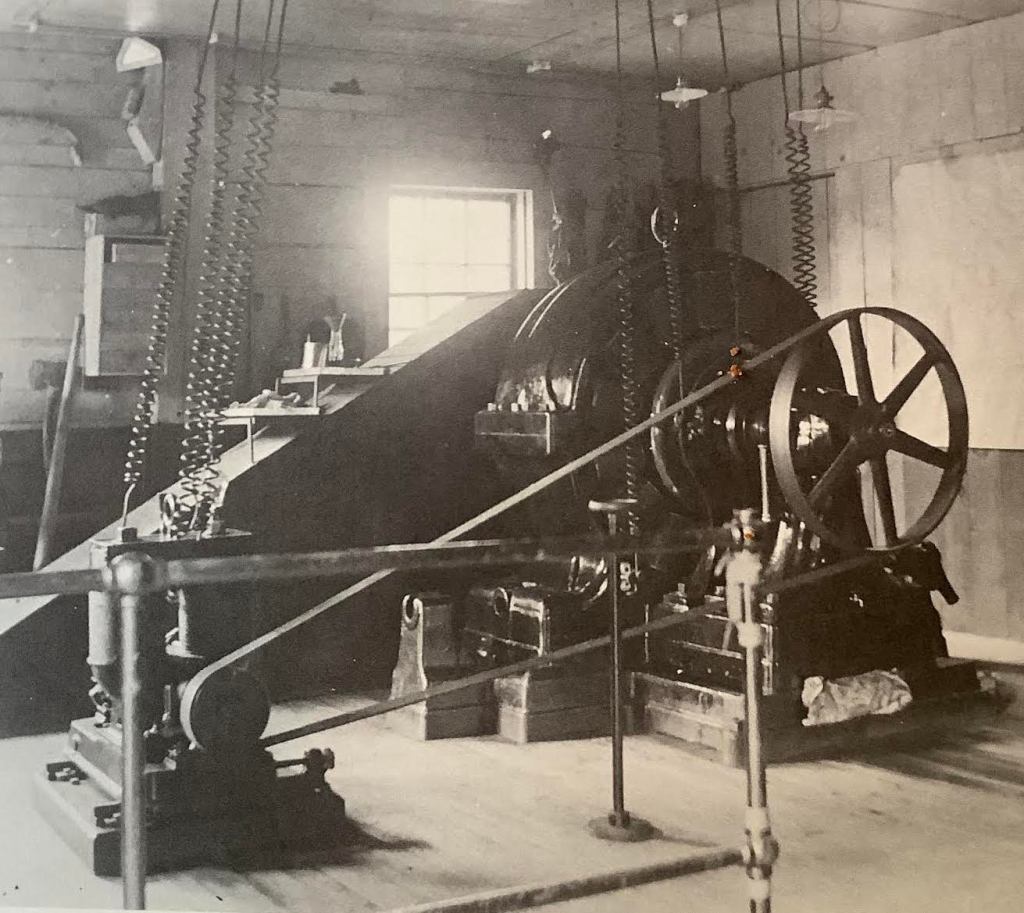

Water had always powered the town’s factories, but that changed in the late 1800s. The water rights to the river bank were formally purchased sometime in the 1870s by the Goodell Company. [The Goodell company was run from Antrim and owned mills in Bennington as well. Goodell was acquired by Chicago Cutlery in 1983.] In the late 1880s, Bennington and neighboring Antrim began a collaboration with Goodell to develop electricity for the towns. A power house was built at the third dam, wooden without and containing the latest of generators inside.

To string the wires, the first poles for electric wires were put up in the center of town, then going down Antrim Road [now called Mill Road] toward Antrim. What an excitement that must have caused! How modern the townspeople must have felt, to know that they were among the first towns in New Hampshire to have electric street lights! Looking at an old photo of the Village Center, we see wooden plank sidewalks, a horse and wagon, and electrical poles. Even the roof of the town Band Stand was used as an attachment for wires. In those days, poles and wires were not something to photo-shop out of your picture — they were an important part of the scene, showing how forward-thinking the town was.

This was not electricity for home consumption. Houses and farms were illuminated by kerosene lamps and lanterns. Many people at the turn of the 20th century feared electricity and would not have wanted it in their homes, preferring the softer glow of the lamp flame. Many of us still use those when the power goes out.

In the 1920s, Goodell’s river rights were sold to the Monadnock Paper Mill and a newer power house was built: the Monadnock Power Station, 1923, followed by the Pierce Power Station. From that point, and up to the 1950s, hydroelectric power provided the majority of the energy needs for the Paper Mill. Electrical power for the town was taken over by Public Service of New Hampshire, now Eversource.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.